Sednaya Prison: The True Face of Secularism in the Muslim World

Unmasking the Brutality of Secular Authoritarianism in the Muslim World

With the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, Syria is confronting the grim legacy of decades of brutal secularist rule. Sednaya Prison, a site synonymous with torture, rape, mass executions, and inhumane conditions, has been opened to the world, exposing the full extent of the atrocities committed under Assad’s secular regime. Known as the “human slaughterhouse,” the prison encapsulates the systematic repression secularism inflicted on Syrians, particularly those whose expressions of religious devotion or dissent were deemed a threat by the regime.

Under Assad’s secularist authoritarianism, overt religiosity itself was a punishable offence. Ordinary acts of faith, such as regularly attending mosque prayers—especially Fajr, the early morning prayer—or growing a beard, were sufficient grounds for suspicion. Frequenting religious gatherings or being perceived as “too pious” could result in arbitrary detention, torture, or even death. In the eyes of the regime, public expressions of Islamic faith were not neutral acts but potential challenges to state control. Sednaya became infamous as a site where countless individuals were incarcerated simply for practicing their religion openly.

As the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) takes control, much of the international focus has shifted toward concerns about “jihadist” governance and its potential impact on the region. This narrative risks overshadowing the immense suffering inflicted under Assad’s secularist regime, which targeted benign religious practices in its broader campaign of repression.

The revelations from Sednaya and the broader collapse of Assad’s regime challenge the oversimplified dichotomy of secularism as inherently progressive and Islamic governance as inherently oppressive. Instead, they demand a deeper reckoning with the crimes committed under the banner of secular governance and how these policies have long eroded trust and stability in Syria and the broader Muslim world. As Syria embarks on this new chapter, the scars of secular authoritarianism remain a stark reminder of the dangers of suppressing a society’s religious and cultural identity.

Syria: The Assad Regime’s Reign of Terror

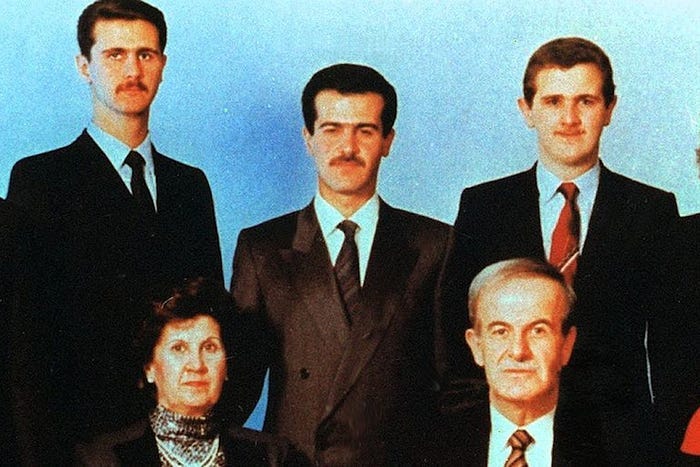

Hafez al-Assad’s rise to power in 1970 marked a significant intensification of Syria’s already entrenched secular authoritarianism under the Ba’ath Party. Long before Assad’s rule, the Ba’athist regime had espoused a secular, nationalist ideology that marginalized political and religious opposition, particularly from the Sunni Muslim majority. Assad’s leadership further consolidated power around the Alawite minority, a sect to which he belonged. Under his rule, the regime deliberately fostered the secularization of the Alawite community, transforming them into a secular bulwark against all other religious groups, particularly the Sunnis, who were seen as the primary political and ideological threat. This strategy deepened the regime’s widespread repression, all under the pretext of preserving national unity and combating religious extremism.

The Hama Massacre: A Defining Atrocity

The apex of Hafez al-Assad’s repression came in 1982 during the Hama Massacre. Triggered by an uprising led by the Muslim Brotherhood, Assad’s forces responded with unprecedented violence. Syrian military units surrounded the city, bombarded residential areas, and conducted door-to-door raids. Over several weeks, an estimated 20,000 to 40,000 Sunni civilians were killed, most of whom were unarmed and unaffiliated with the Brotherhood. The exact death toll remains unknown, as the regime ensured that information about the massacre was tightly controlled.

Reports and survivor testimonies reveal the regime’s deliberate targeting of religious identity during the assault. Soldiers defiled mosques, executed civilians en masse, and scrawled blasphemous slogans like “There is no God but the homeland, and there is no messenger but the Ba’ath party” on the walls of the city. These actions were not just acts of violence; they were calculated attempts to undermine religious beliefs in general, not just those of Muslims or Sunnis. Entire neighbourhoods were flattened, and mosques that had served as community centers were left in ruins.

Hama was not merely a military operation—it was a message. By equating Sunni religious identity with insurrection, the Assad regime weaponized secularism to justify indiscriminate slaughter and the systemic erosion of religious expression.

Blasphemy as State Policy

Hafez al-Assad’s regime also institutionalized practices that forced citizens to conform to its secularist ethos. Public displays of religiosity were viewed as acts of defiance, and devout Muslims were often targeted for surveillance, harassment, or imprisonment. The state-controlled media and education systems propagated a narrative that framed Islamic piety as backwards and subversive, reinforcing the idea that loyalty to the regime was incompatible with faith.

Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian Civil War: Escalation of Secular Repression

Bashar al-Assad, who succeeded his father in 2000, continued and intensified the policies of secular oppression, especially during the Syrian Civil War. While portraying himself as a protector of religious minorities, Bashar used religion as a weapon to suppress dissent and maintain control over the country’s fractured population.

Sednaya Prison: The Human Slaughterhouse

Sednaya Prison emerged as a symbol of the regime’s brutality during Bashar’s rule. Located just north of Damascus, Sednaya became infamous for its systematic torture, starvation, and execution of detainees, many of whom were accused of having Islamist affiliations. Amnesty International estimates that as many as 13,000 prisoners were executed in Sednaya between 2011 and 2015.

Survivor testimonies paint a harrowing picture of the horrors within Sednaya. Detainees were forced to renounce Islam, chant blasphemous slogans, and bow to pictures of Bashar al-Assad as part of their daily humiliation. Religious practices such as prayer were banned, and those caught observing them faced severe punishment or death. The regime’s targeting of religious individuals extended beyond mere political suppression—it was an outright attack on Islamic identity.

Sectarian Targeting and Chemical Warfare

Throughout the Syrian Civil War, Bashar al-Assad’s forces disproportionately targeted Sunni-majority neighbourhoods, further cementing the regime’s sectarian and anti-religious agenda. Barrel bombs and chemical weapons were frequently deployed in Sunni areas, causing mass casualties and displacing millions. The infamous chemical attack on Ghouta in 2013, which killed over 1,400 people, serves as a stark example of the regime’s willingness to use indiscriminate violence against civilian populations.

The regime’s actions also extended to religious infrastructure. Mosques were routinely bombed or repurposed as military outposts, and imams who spoke against the regime faced arrest or assassination. In many cases, religious leaders were forced to publicly support the Assad government or face execution.

A Legacy of Division and Devastation

Under both Hafez and Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s Ba’athist regime weaponized secularism to suppress dissent, destroy religious identity, and maintain authoritarian control. This systematic repression not only devastated Syria’s Sunni population but also eroded the social cohesion necessary for a stable society.

The legacy of the Assads underscores the dangers of imposing secular authoritarianism in a deeply religious society. By treating faith as a threat to the state, the Ba’athist regime alienated large swaths of its population, sowed deep divisions, and laid the groundwork for decades of instability. The horrors of the Hama Massacre, the atrocities of Sednaya Prison, and the widespread targeting of Sunni communities remain stark reminders of the regime’s brutality—and of the broader consequences of using secularism as a tool of oppression.

Contextualizing the Sectarian Criticism

One critique of the assertion that the Assad regime’s brutality stemmed from secular authoritarianism is the claim that its targeting of Syria’s Sunni majority represents a sectarian agenda rather than a purely secularist one. While there is truth to the fact that sectarian dynamics played a role, these actions were primarily shaped by the regime’s desire to maintain power at all costs. The Assad regime’s weaponization of sectarian divisions was a tool of political expediency rather than a reflection of inherent religious bias.

Both Hafez and Bashar al-Assad promoted a Ba’athist ideology that explicitly rejected religious governance. This secular nationalist framework marginalized Sunni Islam as a perceived threat to the state’s unity, much like how other regimes in the Muslim world treated religious identity. Sunni communities bore the brunt of the repression because they formed the majority and had the potential to mobilize opposition. However, this targeting extended beyond sectarian lines: Christian, Druze, and even Alawite individuals who expressed dissent or religious devotion outside the regime’s control faced persecution as well. The regime’s anti-religious actions — such as forcing detainees to renounce Islam, prohibiting prayer, and bombing mosques — transcended sectarian divides, illustrating its broader campaign against Islamic identity.

A Global Pattern of Secular Repression

The brutality of Sednaya Prison and the Assad regime’s oppression are not isolated phenomena but part of a broader pattern across the Muslim world, where secular authoritarian regimes have dominated in modern history. Far more common than Islamic governance, these regimes have repeatedly sought to suppress Islamic identity and expression under the guise of modernization or stability. While some may superficially incorporate references to Islam in their constitutions or rhetoric, such gestures are often secondary to their overarching secularist agendas.

This pattern extends far beyond Syria. In Egypt, secularist leaders like Hosni Mubarak and Abdel Fattah El-Sisi waged relentless campaigns against Islamic political movements while repressing dissent through mass incarceration and violence. In Afghanistan, the communist People’s Democratic Party carried out widespread persecution of religious communities during its secularization campaigns. Turkey, under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his successors, suppressed Islamic practices, banning traditional attire and religious education in their quest for a rigidly secular identity.

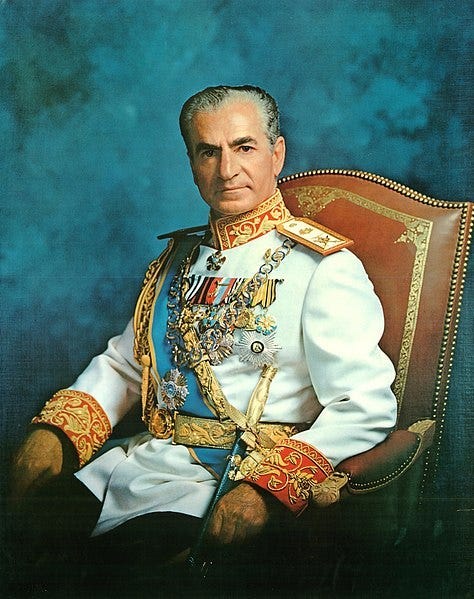

Iran under the Shah provides another stark example. Reza Shah and later his son, Mohammad Reza Shah, aggressively pushed secularization policies. Religious seminaries were closed, Islamic dress was outlawed, and clerics who opposed the regime were imprisoned or executed. This repression fueled widespread resentment, eventually culminating in the Islamic Revolution of 1979, which sought to reclaim Iran’s Islamic identity.

The former Soviet republics in Central Asia—Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan—further illustrate the brutality of forced secularism. During Soviet rule, religious institutions were dismantled, mosques were shuttered, and practicing Islam was criminalized. Even after gaining independence, many of these nations retained secularist authoritarian practices, continuing to monitor and suppress religious activity. For example, Uzbekistan under Islam Karimov arrested and tortured thousands of Muslims on charges of extremism, even for acts as benign as attending regular mosque prayers.

From Libya under Muammar Gaddafi to Iraq under Saddam Hussein, and from Tunisia during the Ben Ali era to the Shah’s Iran, these regimes reveal a consistent pattern of targeting religious communities, pitting religious groups against each other, curbing freedoms, and employing state violence to maintain control. Examining these cases alongside Syria underscores how secularism, far from being a unifying or stabilizing force, has often deepened repression and fueled cycles of resistance and unrest.

Egypt: From Mubarak to Sisi – A Case Study in Secularist Repression

Egypt provides another stark example of how secular authoritarianism has been wielded as a tool of repression in the Muslim world, suppressing political Islam under the guise of maintaining stability and progress. From Hosni Mubarak’s three decades of secularist rule to Abdel Fattah El-Sisi’s rise to power following a military coup, the Egyptian state has consistently targeted Islamic political movements and religious institutions to consolidate control.

Hosni Mubarak’s Reign: Secularism as a Weapon Against Political Islam

Hosni Mubarak, who ruled Egypt from 1981 to 2011, established one of the most enduring examples of secular authoritarianism in the region. His regime systematically repressed religious groups, particularly political ones like the Muslim Brotherhood, using harsh measures to stifle dissent and maintain his grip on power.

Under Mubarak, the Muslim Brotherhood, one of the largest and oldest Islamic political movements in the world, was banned and labelled a threat to national security. Thousands of Brotherhood members were arrested and imprisoned, often without trial. The organization’s charitable and social outreach programs, which had earned it significant grassroots support, were viewed with suspicion, and their leaders were routinely harassed or detained.

Mubarak’s government did not limit his repression to Islamist political organizations, it kept mosques and Islamic schools under tight surveillance, fearing they could become hubs of anti-regime sentiment. Imams were often required to deliver state-approved sermons, and any deviation from the regime’s narrative could result in dismissal or arrest. This level of control extended to Islamic charities and NGOs, which were heavily regulated to prevent them from serving as a base for political organizing.

Mubarak’s policies not only undermined political Islam but also eroded public trust in the state’s ability to represent the interests of its people, setting the stage for the uprisings of 2011.

The Rise of Morsi: A Brief Democratic Experiment

In the wake of Mubarak’s ousting during the Arab Spring, Egypt experienced a brief and unprecedented period of democratic governance. Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, became Egypt’s first democratically elected president in 2012. His victory represented a historic moment for the country.

However, Morsi’s presidency was fraught with challenges. His attempts to implement policies inspired by Islamic principles were met with fierce resistance from Egypt’s entrenched military and secular elite, as well as skepticism from Western powers. This resistance culminated in a military coup led by General Abdel Fattah El-Sisi in July 2013, which ended Egypt’s brief experiment with democratic Islamic governance.

The Coup Against Morsi

The coup against Morsi, widely supported by Egypt’s secular elite and wholeheartedly endorsed by Western governments, marked the return of authoritarian secularism under El-Sisi. The military justified its actions by citing fears of Islamist governance, a narrative that resonated with Western concerns about political Islam.

Following the coup, thousands of Egyptians took to the streets to protest Morsi’s removal. The largest of these demonstrations was held at Rabaa al-Adawiya Square in Cairo, where supporters of the ousted president staged a sit-in. On August 14, 2013, Egyptian security forces launched a violent crackdown, killing over 1,000 protesters in a single day. The Rabaa Massacre, described by Human Rights Watch as a “crime against humanity,” remains one of the darkest chapters in Egypt’s modern history.

El-Sisi’s Reign of Repression And Western Hypocrisy

El-Sisi’s government banned the Muslim Brotherhood outright, designating it as a terrorist organization. Thousands of its members were imprisoned, tortured, or executed, and many others fled the country. The crackdown extended beyond the Brotherhood to include any individual or group perceived as having Islamist sympathies, effectively criminalizing political Islam in its entirety.

El-Sisi’s rise to power and subsequent repression of political Islam received significant support from Western governments, which prioritized secular authoritarianism over democratic principles. The United States, for example, resumed military aid to Egypt shortly after the coup, signalling tacit approval of El-Sisi’s actions. This backing highlights a troubling double standard: while Western powers champion democracy and human rights in theory, they have repeatedly supported secular authoritarian regimes in the Muslim world when the will of the people threatens the status quo.

A Legacy of Betrayed Aspirations

El-Sisi’s Egypt epitomizes how secular authoritarianism prioritizes power over democratic ideals and the well-being of its citizens. The brutal suppression of the Muslim Brotherhood and the broader crackdown on benign religiosity have not only deepened societal divisions but also reinforced that secularism, as practiced in the Muslim world, is inherently repressive.

The story of Egypt, from Mubarak to Morsi to El-Sisi, underscores the broader pattern of secular regimes in the region: the marginalization of Islamic identity, the suppression of political dissent, and the reliance on Western support to maintain authoritarian rule.

Afghanistan: Communism, Secularism, and the Assault on Islamic Identity

Afghanistan’s experience with communism and enforced secularism provides a chilling account of how leftist ideologies have sought to repress Islamic identity and erode cultural and religious traditions. From the rise of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) to the Soviet invasion, Afghanistan became a battleground for ideologies that sought to secularize its deeply religious society forcibly.

The PDPA and the Campaign for Secularization

In April 1978, the PDPA, a Marxist-Leninist political party, staged a coup and overthrew Afghanistan’s ruling monarchy, marking the beginning of a period of aggressive secularization and leftist authoritarianism. The PDPA aimed to transform Afghanistan into a socialist state, viewing the country’s Islamic traditions as obstacles to modernization.

Attacks on Islamic Education and Institutions: The PDPA banned religious education, a cornerstone of Afghan society, replacing it with state-controlled curricula that promoted Marxist ideology. Islamic courts, which had long served as arbiters of justice in the country, were dismantled and replaced with secular legal systems designed to enforce the regime’s vision of progress.

Islamic scholars and clerics, seen as ideological adversaries to the PDPA, were targeted for arrest, torture, and execution. The regime sought to eliminate the influence of religious leaders, who were among the most vocal critics of the PDPA’s policies. Thousands of clerics were killed, and many more were imprisoned or forced into exile.

The Soviet Invasion: Amplifying the Repression

When the PDPA faced growing resistance from Afghanistan’s rural population, the Soviet Union intervened militarily in December 1979 to support the faltering regime. The invasion triggered a brutal decade-long conflict that intensified the repression of Afghanistan’s Islamic identity.

Counterinsurgency Campaigns and Mass Killings

The Soviet military, alongside PDPA forces, conducted scorched-earth campaigns against Afghan villages, targeting areas that were perceived as hubs of resistance. Over a million Afghans were killed during these operations, with countless others maimed or displaced. Bombings, massacres, and the use of chemical weapons were among the tactics employed to crush the mujahideen, Islamic fighters resisting Soviet rule.

Cultural Erasure and Marxist Indoctrination

The Soviets sought to dismantle Afghanistan’s Islamic traditions and replace them with Marxist-Leninist ideology. Religious practices were discouraged or outright banned, while Soviet propaganda infiltrated education, media, and public life. Islamic symbols were systematically removed, and attempts were made to instill loyalty to the communist regime among Afghan youth.

The Resistance: Islam as a Unifying Force

Afghanistan’s resistance to the PDPA and the Soviet invasion became a rallying cry for Islamic movements worldwide. The mujahideen, comprising diverse groups united by their Islamic faith, mobilized to defend their homeland against foreign domination and ideological subjugation.

The mujahideen framed their struggle as not merely a fight for national liberation but also a defence of Islam against an ideology that sought to erase it. The resistance drew support from Muslim-majority countries and communities globally, reinforcing the centrality of religion in the Afghan identity.

The PDPA’s secularist experiment left a legacy of deep scars in Afghanistan. By attempting to impose Marxist ideals on a population with a profoundly Islamic identity, the regime alienated its people and fueled a resistance that ultimately led to its downfall. The Soviet invasion, intended to stabilize the PDPA’s rule, only amplified the suffering and resistance, further demonstrating the failure of forced secularization.

Decades later, the United States would fail to learn from its Soviet adversary’s mistakes, repeating many of the same errors while committing atrocities on an even greater scale under the guise of liberating Afghanistan and promoting secular governance. Despite the devastation wrought by both Soviet and American interventions in the name of secularism, these atrocities are seldom acknowledged in Western narratives. Instead, discussions of Afghanistan’s struggles disproportionately focus on the Taliban’s governance and Islam, ignoring the role of foreign interventions in destabilizing the country and shaping its political trajectory.

The Shah of Iran: Secularization and Brutal Suppression

The rule of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran (1941–1979), is a defining example of how forced secularization and authoritarian governance can destabilize a nation and provoke widespread dissent. Under the guise of modernization, the Shah imposed a Westernized vision on Iran, marginalizing its Islamic identity and violently suppressing opposition. His policies not only alienated the predominantly Muslim population but also laid the groundwork for the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Forced Secularization: The White Revolution and Beyond

The Shah’s modernization program, known as the White Revolution (1963), was a centrepiece of his effort to transform Iran into a secular, industrialized state. Backed by Western powers, particularly the United States, the Shah pursued policies that undermined Iran’s Islamic and cultural traditions.

The White Revolution’s land redistribution policies were designed to weaken the influence of the traditional clergy, who often held substantial sway over rural communities. The clergy’s role as mediators and leaders in these areas was eroded, creating resentment among both religious leaders and their followers.

The Shah aggressively promoted Western cultural values, often at the expense of Islamic practices and traditions. Traditional Islamic attire, particularly for women, was discouraged, and public observance of Islamic rituals was undermined. The regime sought to replace Iran’s religious identity with a secular, Westernized one, alienating vast swathes of the population.

Islamic institutions and clerics who resisted the Shah’s policies faced severe repression. Mosques, religious schools, and seminaries were closely monitored, and dissenting religious leaders were silenced through imprisonment, exile, or execution.

Repression of Dissent

The Shah’s secularization efforts were enforced through a brutal apparatus of surveillance and repression, epitomized by SAVAK, his notorious secret police. SAVAK played a key role in silencing political and religious opposition.

Prominent Islamic figures who opposed the Shah’s policies, such as Ayatollah Khomeini, were targeted. Khomeini, who would later lead the Islamic Revolution, was exiled for his outspoken criticism of the regime.

Individuals who engaged in religious activism or promoted Islamic governance were labelled as extremists and subjected to harassment, arrest, and torture. Public displays of religiosity, such as frequent mosque attendance, were viewed with suspicion.

Established with the help of the CIA and Mossad, SAVAK was infamous for its methods of torture, arbitrary detention, and extrajudicial killings. Thousands of political dissidents, many of them religious activists, were imprisoned or executed under its watch.

Economic Disparities and Cultural Erosion

While the Shah’s modernization efforts brought some economic benefits, they were unevenly distributed, exacerbating economic disparities. Urban elites benefited from industrialization and Westernization, while rural and working-class populations—deeply tied to Islamic traditions—felt left behind.

The Shah’s policies created a stark divide between the urban, secular elite and the rural, religious majority. This disconnect deepened the sense of alienation among the population, as they saw their Islamic values being systematically eroded.

The traditional bazaar merchants, who were closely linked to the clergy and Islamic culture, faced economic and political marginalization under the Shah’s modernization initiatives.

The Fallout: Seeds of Revolution

The Shah’s forced secularization and authoritarianism ultimately backfired, as they alienated the very population he sought to modernize. The repression of religious identity and the marginalization of Islamic traditions fueled a growing resistance movement.

By the late 1970s, a coalition of religious leaders, students, and working-class citizens rallied around Ayatollah Khomeini, whose calls for an Islamic government resonated with the disenfranchised population. The Shah’s regime collapsed in 1979, and Iran was transformed into an Islamic Republic.

Lessons from the Shah’s Reign

The Shah’s aggressive secularization policies, enforced through brutal repression, demonstrate the dangers of ignoring the religious identity of a nation. His attempts to impose Western ideals on a deeply Islamic society not only failed to achieve stability but also catalyzed one of the most significant revolutions of the 20th century.

The case of the Shah underscores a broader pattern in the Muslim world: secular authoritarianism, whether leftist or right-wing, leads to repression, alienation, and eventual upheaval. The forced marginalization of Islam as a societal foundation does not lead to progress but to resistance, instability, and cycles of violence.

Conclusion: A Century of Secular Repression in the Muslim World

The case studies of Syria, Egypt, Afghanistan, and Iran are but a small sample of the brutal secular regimes that have dominated the Muslim world since the fall of the Caliphate in 1924. These nations represent the breadth and depth of secular authoritarianism's impact—imposing repression, curbing freedoms, and erasing Islamic identity under the guise of modernization, stability, or alignment with global powers. Yet, they are far from alone in this legacy of suppression.

In Pakistan, the secular military elite has historically wielded significant power, systematically sidelining aspirations for Islamic governance and pursuing policies more aligned with Western geopolitical interests than with the religious and cultural values of its population.

In Bangladesh, the secular nepotistic ruling class—particularly under Sheikh Hasina—has stifled Islamic movements, curtailed religious freedoms, and criminalized dissenting voices, often branding them as threats to national stability.

Meanwhile, the Gulf monarchies, despite their outward displays of Islamic symbolism, have functioned less as custodians of Islamic principles and more as enforcers of Western economic and political agendas. They suppress genuine Islamic governance and discourage the nurturing of Islamic values within their societies, focusing instead on projecting an image that placates international allies while alienating their own religiously inclined populations.

These regimes, whether explicitly secular or masking their secularism with “Islamic-inspired” veneers, have consistently worked to suppress Islamic movements, values, and institutions. Their actions reflect a broader pattern of forced secularism imposed upon the Muslim world, often at the behest of foreign powers. This systemic repression is neither coincidental nor organic—it is a deliberate effort to reshape Islamic societies according to secular and Western ideals, regardless of the societal harm it inflicts.

The Double Standard: Secular Failures vs. Islamic Governance

At best, modern Iran and Afghanistan stand as the only significant non-secular states in the Muslim world. Critics of Islamic governance often cite them as evidence of its failure. However, such an argument is profoundly unbalanced. Suppose the challenges and shortcomings of these two nations are enough to discredit Islamic governance. In that case, the overwhelming failure of the dozens of brutal and oppressive secular regimes in the Muslim world should more strongly discredit secularism.

Islamic governance has been the foundation of the Muslim world for 14 centuries. It created a civilization that was not only a beacon of knowledge, trade, and culture but also a sanctuary for religious minorities. Jews, Christians, Zoroastrians, and others flourished under Islamic rule, living and worshiping freely in lands governed by Sharia. It is only in the secular age, after the dismantling of Islamic governance structures, that religious minorities have come under consistent and systemic threat in the Muslim world.

Contrast this with the history of Europe and North America. Until the recent influx of immigrants from the Global South, these regions were largely religiously homogenous, a condition achieved through centuries of forced conversions, expulsions, and genocides that ensured the dominance of a single religious or cultural identity. This homogeneity laid the groundwork for secularism to emerge and thrive, as the absence of significant religious diversity reduced the risk of deep-seated tensions or competing identities undermining the system.

In stark contrast, the Muslim world has historically been a mosaic of religious and cultural diversity, coexisting for over a millennium under Islamic governance systems that often prioritized pluralism and the protection of minority rights. Attempts to impose secularism in these societies—such as in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey—have frequently required the suppression or forced homogenization of religious and cultural identities as a precursor. This is because secularism, in practice, demands a neutral "common ground," which in diverse societies translates into the marginalization of competing religious expressions to achieve a superficial sense of unity.

Rather than fostering coexistence, these secularizing efforts have pitted groups against each other, exacerbating sectarian divides and sowing discord. In Syria, for example, the Ba'athist regime suppressed Sunni Islam while attempting to reshape the Alawite identity into a secularized bulwark against other faiths. In Iraq, the post-monarchy push for secular nationalism marginalized religious identities and fractured the social fabric. These examples demonstrate that secularism, which succeeded in the West due to pre-existing homogeneity, struggles to function in truly diverse societies like those in the Muslim world, where it often leads to repression and societal fragmentation instead of unity.

The True Legacy of Secularism in the Muslim World

This contrast highlights an uncomfortable truth: while secularism is often touted as a universal model for governance, its success relies heavily on conditions of religious uniformity that the Muslim world neither historically pursued nor naturally possesses. Instead, it is Islamic governance that has demonstrated a far more robust track record of accommodating diversity and fostering coexistence without erasing differences.

The narrative that secularism is a universal path to progress and stability in the Muslim world crumbles under the weight of historical evidence. The realities of forced secularization—repression, instability, and the erosion of societal values—have proven more destructive than the perceived failures of Islamic governance. The Muslim world's historical experience under Islamic rule demonstrates that it is not Islam, but secular authoritarianism, that has been the root cause of its suffering in the modern age. Sednaya Prison, a symbol of this secular brutality, serves as a stark reminder of the oppressive realities behind the facade of secular governance.